I gained access to RabbitMQ brokers multiple times for the past year during pentesting engagements. It was always due to default credentials (the infamous guest:guest) or credentials being leaked in some way (e.g. in publicly accessible .env file).

The problem when you discover a RabbitMQ service is that you can’t really dump content as you would with, let’s say, a database back-end. You need to know the exact names of virtual hosts, exchanges, and routing keys in order to be able to consume messages being sent through. Listing those values not being implemented by AMQP, you’re left completely blind.

This leads to situations where it is quite difficult to prove the impact of a compromised RabbitMQ instance to a client:

Tester: we gained unauthorized access to your RabbitMQ broker

Client: ok. what did you extract from it ?

P: well, we were not able to capture any message so …

C: how is that high severity then ?

While accessing the source code of clients connecting to the broker is a way to gain enough knowledge to capture content, it is almost always impossible in black box scenarios. Another way - which is the one I explore in this post - is harnessing the API exposed by the rabbitmq_management plugin.

I won’t go into RabbitMQ details so I suggest you to read those excellent tutorials if you do not have prior knowledge.

rabbitmq_management

rabbitmq_management is a RabbitMQ plugin that will spin up a web server with both a REST API and an administration GUI. You can use the GUI or interact directly with the API to manage pretty much everything. Due to its ease of use, a lot of developers use it so they don’t have to learn all the rabbitmqctl commands. For every RabbitMQ listener publicly exposed I encountered so far, rabbitmq_management plugin was also enabled.

What we’re interested in with rabbitmq_management is the REST API it exposes. We will use it to obtain a bunch of information about the server. Namely:

- a list of vhosts

- a list of queues per vhost

- a list of exchanges per vhost

- a list of clients currently connected to RabbitMQ (bindings)

- exposed network listeners (AMQP, AMQP/SSL, Erlang replication)

- miscelaneous information (node name, RabbitMQ version, Erlang version)

Once we have all that information, we will start consuming everything by following this methodology:

- gather information by sending requests to rabbitmq_management REST API.

- launch one process per vhost

- each process establish a connection and open a channel within that vhost

- within that channel, the process will bind to every queue and every exchange following a strict capture model

What do you mean by “capture model” ? Well, I’m glad you asked :)

Capture models

Our objective is to capture messages being sent through while limiting our impact on the target’s availability. This means currently connected clients need to receive messages as if we were not capturing them.

If we don’t take care of that and clients were written without much thinking, you will end up with a completely messed up target such as queues stacking up because clients stopped processing given item X was not received, hanged RPC clients because you captured the request without forwarding it to the RPC server, integrity violations triggered by clients pushing data not received in order. Sky is the limit when it comes to doom scenarios.

Let’s see how we can handle all of this by analyzing each RabbitMQ’s mode of operation!

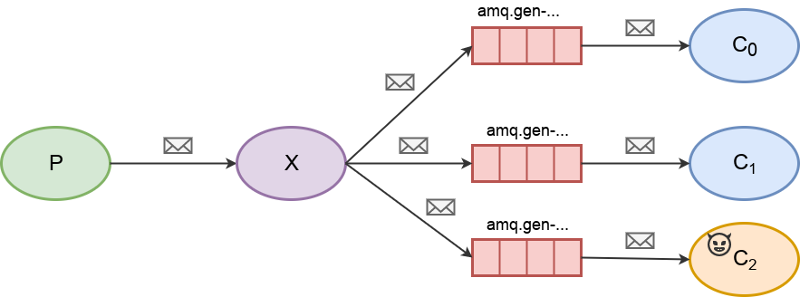

Producer Consumer Model / RPC Model

In the producer consumer mode, our connection will just move the model towards the Work queues model with legitimate consumer (C0) being one worker and ourselves (C1) being a second worker. The interesting thing here is that as soon as we receive our first message and re-queue it (yellow mail), we will be able to capture all of them due to the round robin distribution implemented by RabbitMQ. Think about it: if we re-queue fast enough we will always be the next client in the round-robin queue. In the end, it is as if we were diverting all messages through the red line (see my wonderful GIF above) to transparently log them without impacting the legitimate consumer.

This capture model also applies to RPC calls. We just need to re-queue messages with their complete meta-data (properties such as reply_to, correlation_id, timestamp, or expiration) so that the RPC server ultimately receives the request as if it were coming from the RPC client. Consider it ‘RPC call spoofing’ if you will.

Note that with traffic intensive queues, it is entirely possible to miss a beat (a message being dispatched prior to our script re-queueing the previous one). The legitimate client will never miss a message that was intended for him but we, as attacker, might miss some.

Edit (18/09/2017): I initially relied on rabbitmq_management API to check if other consumers were present to know if I should re-queue a message or not. This was generating an insane amount of HTTP requests towards the target so I searched for a more clever solution. The solution I came up with is this: always re-queue received messages, but insert a random and unique header in the message prior to re-queuing it. Upon message reception, if our unique header is present this means we are the only consumer so we don’t re-queue again. No more HTTP requests and only 1 unnecessary publish action if we are the only consumer (which is an obvious edge case).

Work queues

The description for the Producer Consumer model above applies to this capture model, the only difference being the amount of consumers bound to the queue. Assuming RabbitMQ is configured by default and distribute messages to consumers in a round robin manner, you will be able to capture len(messages)/len(consumers)-1 messages. The less consumers there is, the more we are able to capture.

Assuming we have administrative privileges, an aggressive way to ensure we get all messages would be to disconnect all consumers but one using the rabbitmq_management API. However, this could lead to denial of service condition if work load gets dispatched to a single node that can’t handle it.

Fanout exchange (a.k.a publish/subscribe)

In this capture model, we simply bind a queue to the fanout exchange. All subscribers bound to the exchange will receive all messages, including us.

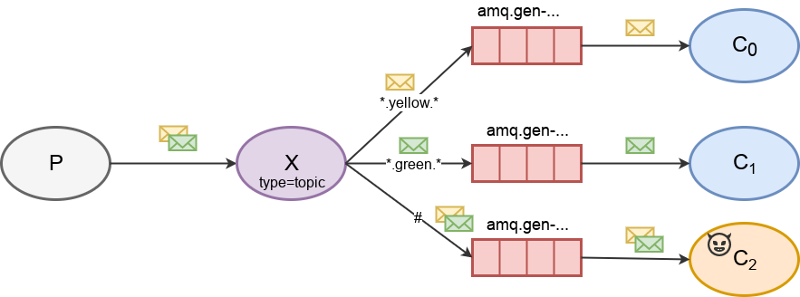

Topic exchange

In this capture model, we bind a queue to the topic exchange using a wild-card (#) routing key in order to receive all messages.

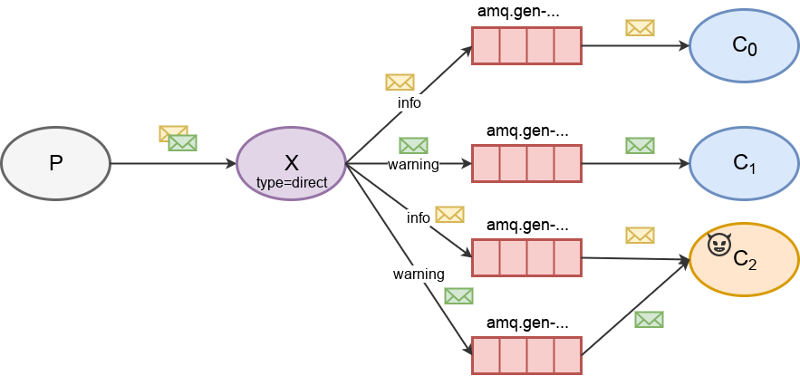

Direct exchange

Direct exchanges do not support wild-card (#) routing keys. Therefore, we list bindings between other consumers and this direct exchange to obtain a list of routing keys currently in use by consumers. Then, we bind one queue per discovered routing key to the direct exchange. This way we are able to receive the same amount of messages as all consumers bound to this direct exchange combined.

Note: some producers might send messages with a routing key unused by currently bound consumers. Still need to think about that scenario.

Exploitation scenario

Some scenarios I have observed and executed, some just floating in my head:

- Information disclosure: captured messages can contain user’s data, user’s locations, credentials, …

- Injection attacks: message data used in SQL queries, serialized objects sent within message body, …

- Spoofing attacks: imagine authentication implemented with RPC - you could spoof the RPC server, replying with the right content to get in. Or imagine a worker queue that generates PDF files where you could feed it your own URLs back

Enter Cottontail

I wrote a tool that implements everything I just described, called Cottontail. It is available on Github: https://github.com/QKaiser/cottontail

It is pretty straightforward. You launch it by providing a URL to a rabbitmq_management server and it will try to connect using default credentials (you can change that behavior using --username and --password):

$ python main.py

/\ /|

\ V/

| "") Cottontail v0.4.0

/ | Quentin Kaiser (kaiserquentin@gmail.com)

/ \\

*(__\_\)

usage: main.py [-h] [--username USERNAME] [--password PASSWORD] [-v] url

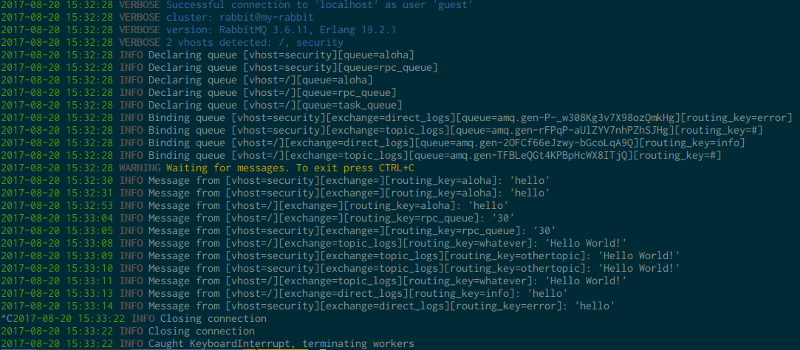

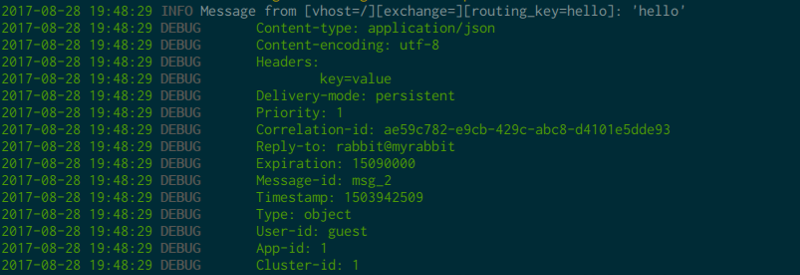

It will then proceed, following the methodology stated above, and log received messages along with their vhost, exchange, and routing key:

If you are really curious you can activate the verbose mode with -v, it will force cottontail to print out message properties and headers:

Of course, do not hesitate to file an issue or to submit a pull request :)

Assessing exposure

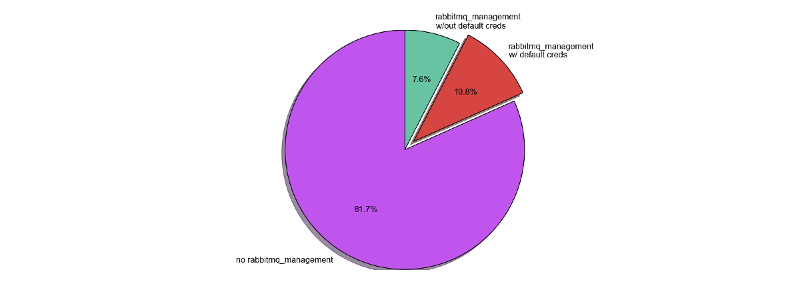

I wanted to see how exposed are RabbitMQ brokers over the Internet. I started by downloading a list of hosts exposing an AMQP listener on port tcp/5672 from Shodan and proceeded by scanning port tcp/15672 (rabbitmq_management_plugin/plain) and port tcp/15671 (rabbitmq_management_plugin/ssl) on those hosts.

Out of 4813 hosts exposing port tcp/5672, 832 are exposing port tcp/15672 only and 50 are exposing both ports tcp/15672 and tcp/15671. Out of those 882 hosts exposing a rabbitmq_management_plugin, 518 are allowing connections from the Internet with default credentials (guest:guest). To sum it up, 18,32% of exposed RabbitMQ brokers have rabbitmq_management_plugin installed, 58,73% of which allows connections with default credentials over the Internet.

Conclusion

I hope this post motivated you to learn more about RabbitMQ and message brokers in general as they are more and more a key component of modern web application stacks. I also hope that my tool will facilitate the work of pentesters and web application auditors alike when they are faced with a RabbitMQ instance.

Some key recommendations for people administering RabbitMQ clusters:

- do not expose your AMQP listeners to the Internet unless it is a hard requirement. If so, implement access control lists to limit exposure (iptables is your friend here).

- do not expose rabbitmq_management to the Internet unless it is a hard requirement. If so, implement access control list to limit exposure.

- delete the guest user or at least change its password to a unique, complex, and random value

- implement and review your RabbitMQ access controls (see https://www.rabbitmq.com/access-control.html)

That’s all folks ! :)